|

WATCH THIS! If I do say so myself, it is an awesome video!

2 Comments

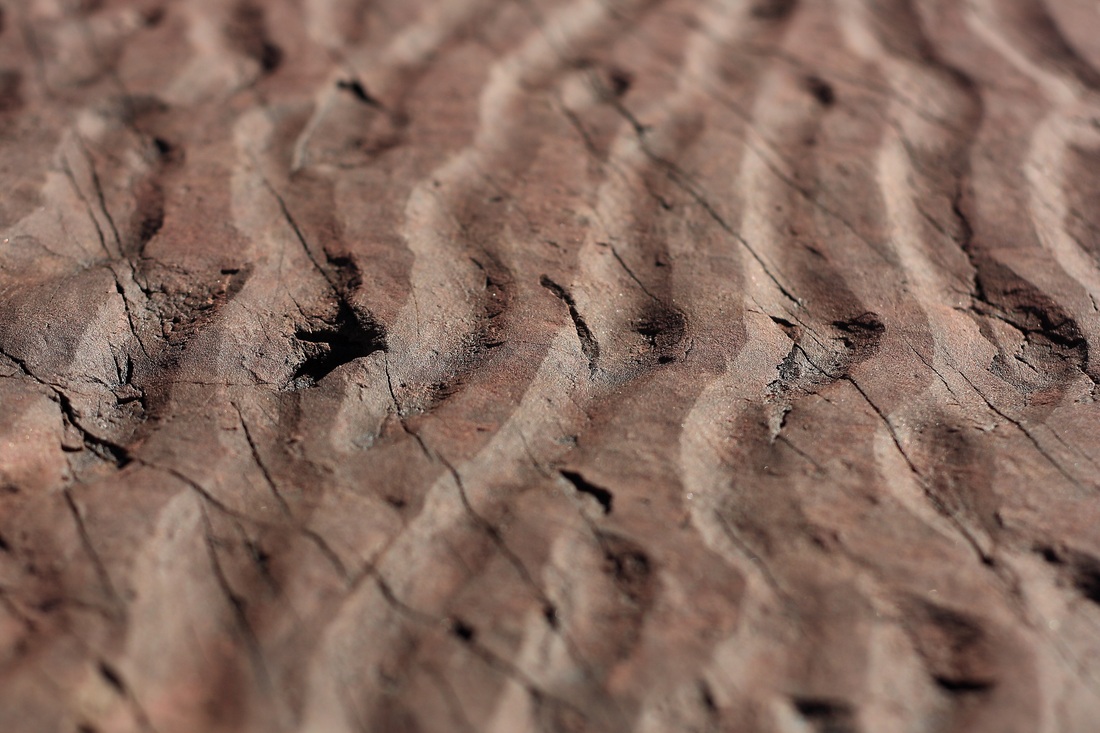

"The Canyon giveth, the Canyon taketh away" Just two days after visiting Glen Canyon Dam to watch the beginning of the High Water Flow experiment, Peter, John, Ana, Scott, Jason, Jeff, and I loaded up our weekpacks and started off down the New Hance Trail into the Grandest of Canyons. Google the New Hance trail and I am sure you will get a bunch of rants about how it is the most absurd thing that ever existed, or at least the most absurd thing that is actually called a 'trail'. My own conviction on the matter is that you aren't hiking unless there is a bit of class 4 involved (you are just strolling). Needless to say, I thoroughly enjoyed the decent into Red Canyon, which weaves and winds down through the Kaibab and Toroweap limestones, the Coconino sandstone, the Hermit shale, the Supai supergroup, the Redwall limestone, the Muav limestone, the Bright Angel Shale, and the Tapeats sandstone. The trail ends by Hance Rapid on the Colorado River after culminating in some AMAZING dry-creek hiking through the bottom of Red Canyon (which I accidentally called Hance Canyon in this video). I LOVE boulder-hopping and downclimbing the grand and colorful boulders of that place. While I was there, I ran a few experiments on the local hydrology. With the High Flow Experiment still in operation, the river level was WAY HIGH. Trees, trails, and the famous invasive plant called the Tamarix were all underwater, which made for very interesting hiking (or should I say climbing) the next day, and also forced us up onto a high beach to camp for the night. We ended up in a righteous campsite tucked underneath a maze of twisting tree branches that made for a great kitchen/closet/living room. Immediately upon arriving at camp, Springs basically curled up and started napping. I told him that was a dumb idea because he missed an AWESOME view of the moon coming out. He wasn't much help in the morning either - he pretty much climbed up in a tree and watched me pack and do all the work. As I have alluded to previously, the Canyon was formed by a number of geological processes. The first was the original deposition along the sea floor of sand, mud, and the skeletons of ocean-dwelling invertebrates. Over time, these materials were buried and 'lithified' (turned into rock) under high pressures. The land then rose (it was 'uplifted'), allowing for the development of a river which then downcut through what is now the Grand Canyon. Finally, erosion also occurs on the edges of the Canyon, constantly whittling away at the sides of the giant hole in the ground. The result is a number of interesting rock types and structures. You may see the 700 million year old ripple marks now frozen in time. Shale layers may flake off one at a time, each representing a number of years beyond the human ability to comprehend. Sandstones may show interesting layers also, which could be a clue as to a different environment at the time of deposition - though bends and curves in these layers may have formed while the sand was being lithified, far under the ground and under high pressures and temperatures. It is the challenging job of scientists to interpret all of these clues as to what the past was like, and they use a stunning number of ingenious techniques to understand and interpret the different processes that make these rocks into what we see today. Rocks aren't the only interesting science to be found in the Canyon. The harsh desert environment makes living a struggle for any type of life, and the adaptations that plants and animals make in order to adapt and thrive are nothing short of astonishing. Some of my favorite plants are the cacti, which in order to adapt to the lack of water have lost true leaves, which are a characteristic trait of many plant species throughout the world. Instead, the cactus retains only spines, which serve many purposes including water retention. To me, the most amazing trait of cacti in the Grand Canyon is the massive diversity of the plants - there are all different types in different locations; if Darwin would have visited this place he would have never had to wait to publish his theories! It would have been just too obvious. On Thanksgiving Day we made our way across Papago Creek, which is certainly another one of my happy places. I took the time to drop my pack and explore the creek for a while. At the mouth of the dry creek, there was another canyon slide that was too intense for me to do, because in the world's biggest playground it's a long way from help if you are stupid and hurt yourself. Again, the Canyon givith (to those who are respectful), and the Canyon taketh away (from those who aren't). I climbed back out of the creek and walked around to get a good feel of just how big it was from the front also. It was a very nice drop. After Papago Creek comes a bit of a traverse across cliffs above the river, followed by a hike up the beginning of 75-mile canyon. The high canyon walls make the place feel like home. The exit out of the canyon includes a great bit of full-pack, low-grade 5th class climbing. Super fun. On Thanksgiving night, we enjoyed another great moon. Oh yeah, and a TON of Thanksgiving food - turkey, stuffing with butter, green beans, cranberries, and even pumpkin pie, whipped cream, and eggnog! We cooked it over good old homemade alcohol stoves made from old beer cans, of course. A few Grand Canyon hikers happened to be at the same beach as us, so we invited them down for the festivities. One father was hiking with his middle school aged daughter, so they were especially timid to come down and celebrate the holiday with a bunch of eggnog- and bourbon-drinking crazy hikers. But, the smell of pumpkin pie rapidly melted their timidness, and all of us agreed we had never seen such a happy 14-year-old after she had 3 pieces of pie. Later on I played with taking some night pictures in my eggnog-induced stupor. We awoke, feeling fresh and ready to go... kind of. :) We hiked to Cardenas Beach, where we camped for the night. Throughout the time we were there, water levels were still dropping, and by the morning we were able to see some really impressive results of the HFE - beaches had built up to impressive levels. We started our ascent to the top of the Redwall along the Tanner Trail, being constantly rewarded with great vistas and cool views of century plants. As always, when it came time to leave, we just weren't ready to go. Though we had dreamed all week about the steaks and ice cream that we would eat at the end of the trip, they just didn't seem that appetizing anymore. Nonetheless, we packed our bags, hacked, and hiked out of the Grand Canyon. That's it for now, folks. Until next time, happy journeys.

"Education is like water flowing on rocks. The effects are hard to notice immediately, but years from now the results will be unmistakeable" On Monday, November 19th of 2012, my students and I witnessed a historic event and a ... concrete ... reminder of the power humans have to alter our environmental surroundings. It was the first High Flow Experiment of a new series of such experiments, and we were invited to attend the event through a series of pretty lucky connections. When I think of the Colorado River, I rarely ever say the name with out the adjective 'mighty' applied in front of it. The river simply seems so wild and so rugged - it is a symbol of the Wild West. But the sad truth of the matter is that the modern day Colorado River, as compared to its former grandeur, is a poodle in comparison to a wild wolf. The similarities are there and the form and shape is the same, but ... well... you get the point. Let's put it this way: the Colorado, in its natural state, had the erosive power to cut through a vertical mile of solid rocks and form the Grand Canyon over just 6 million years. Natives and explorers who saw and lived on the river in its natural state noticed the dark red color of the river (as evidenced by its name - Colorado meaning "Red" River) that was a result of the massive amounts of suspended sediment (aka chunks of broken rock chopped off from the surrounding walls by the fast flowing river). Ask anyone who has seen the Colorado River flowing through the Grand Canyon - it is a dark blue. That color isn't quite living up to the river's name... Why is the once-red river tinted blue? Well, the short answer is dams. These massive concrete structures - the most famous being Hoover Dam and Glen Canyon Dam - block all water in the river from flowing. The water backs up and creates a huge lake (called a reservoir) upstream from the dam. As you can imagine, water that is still cannot continue to carry sediment downriver. The sediment sinks to the bottom of the reservoir, and the water that is released from the dam continues on downstream clear, blue, and free of sediments. According to the Glen Canyon Institute, 100 million tons of sediment is piled up behind Glen Canyon Dam annually. That's 30,000 dumptruck loads of sediment every day. That means that Lake Powell (the reservoir created by Glen Canyon Dam) could fill up completely in just 300 years - a blink of time geologically. We will eventually have to tend to this concern, and as the Glen Canyon Institute notes, the longer we wait, the more expensive it will be. The water downstream of the dam isn't just sediment-free; it's cold. Whereas the river water's temperature should naturally fluctuate with the changing seasons, the water released from the dam comes from the bottom of Lake Powell where water never sees the sun. This perennially cold water exits the dam spillways all year round just above the freezing temperatures. Another major dam-induced change to the Colorado River is the absence of floods. Historically, springtime snowmelt and summer monsoons would cause fluctuating river levels that redistributed sediments and actually supported native fish species. Luckily, the dams along the river are capable of periodically releasing high amounts of water, which can simulate the conditions of a natural flood. This is the reason my students and I visited Glen Canyon Dam on the 19th - it was the dawn of a new protocol in High Flow Experiments (HFE's) on the Colorado River. HFE's have been conducted on the Colorado before - first in 1996, and then again in 2004 and 2008. As you notice, the events were spread out with several years between experiments. Furthermore, the experiments were run basically when the political and monetary concerns were worked out. Under the new protocol for HFE's, the timing of the flood events will be driven by science instead of policy. This means floods will occur when we know they should based on the environmental conditions, and they will be strategically timed with the 'sediment trigger' - a time when the river will be able to most effectively capture sediments and redistribute them for the benefit of native wildlife species and recreational river users. The event was certainly educational for us, and while we were there we got to meet the Secretary of the Interior, Ken Salazar. Even more impressive for me was meeting the Director of the National Park Service, Jon Jarvis, who was a totally down-to-earth person who LOVES his job - an inspiration! One of our students even got picked up by Secretary Salazar! We still haven't quite figured out why!

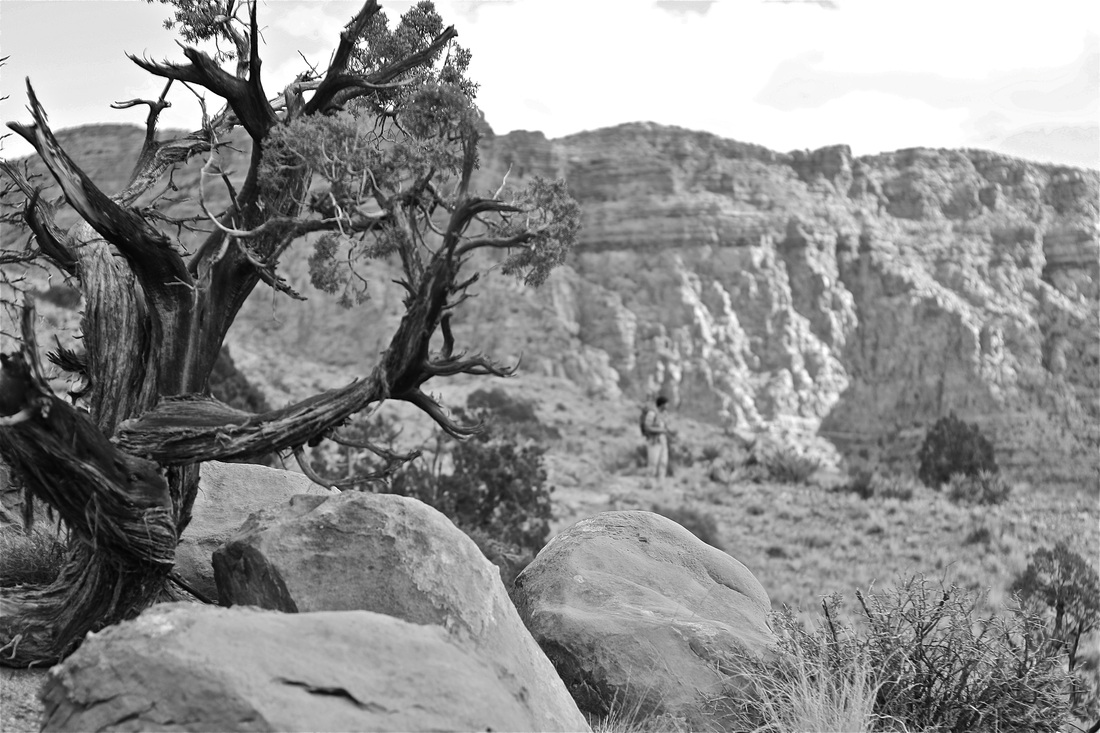

Felipe and I joined Peter and Ana on a day-hike down the Tanner Trail last Saturday. We carried down eight and a half gallons of water, 18 beers, and a bottle of bourbon to stash a cache for our upcoming Thanksgiving hike. Oh give us a break - like you won't indulge yourself over Thanksgiving weekend! The white, puffy clouds warned of rain and dotted the landscape with shadows, but we never felt more than a few drops hit our skin and the shadowed landscape highlighted the beauty of the natural colors of the Canyon. I am trying to learn a bit more about photography and taking cool pictures. Today, I posed a challenge to myself... take all my pictures in black and white. The Canyon is a good place to do this because of the texture of the landscape... folds and cracks in the rocks and gnarled junipers can stand out even more in black and white than in color. So, my challenge was essentially to find texture in the landscape that out-shaded the brilliantly rusty colors of the Canyon and the clear blue of the Colorado River and the sky. The photography challenge was fun, but I mean it when I say you should have seen it in color. |

Authormarshall moose moore is a meandering biogeochemist (a type of environmental scientist who studies elemental cycles) who is always on the lookout for good stories. The blog is a place to tell some of those fun stories. Check out The Course or The Brave Monkeys Speak Podcast for lessons and actionable goals to apply to YOUR life. The Life-Adventurer's Manifesto:

Categories

All

Popular Pages:

|

|

|